Closing Navigation Locks in the Upper Mississippi—and the Snake?

The lock at Upper St. Anthony Falls (foreground), with a flow of ~26,000 cfs over the dam (background). Photo S. Anisfeld.

In 2015, the Upper St. Anthony Falls Lock on the Mississippi River in Minneapolis (shown)—the uppermost and deepest lock in the Stairway of Water—was closed permanently in order to prevent invasive carp from moving up into the headwaters of the Mississippi River and Minnesota’s famous lakes. The lock is still being used to discharge water during flood flows on the river (and the dam is needed to protect the water supply for Minneapolis) so there are no plans to remove it. But the benefits of navigation were simply not worth the ecological risk.

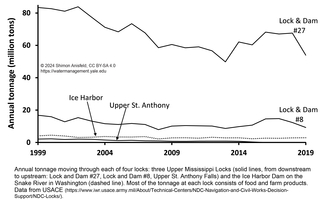

A look at lock traffic can help us think through whether other locks are likely to go the way of Upper St. Anthony. The figure to the left shows that traffic through the most downstream lock on the Upper Mississippi (#27) is still strong, although with some decline over the last decades. As we move up the river to Genoa, Wisconsin (Lock and Dam #8) and Minneapolis (Upper St. Anthony), traffic decreases, so closing the Upper St. Anthony Falls Lock was a relatively easy decision.

The next “easy” decision might be on the Snake River (a tributary of the Columbia) in eastern Washington, where traffic through the Ice Harbor Dam—the most downstream of four dams that allow navigation along the Snake from its confluence with the Columbia to Lewiston, Idaho—is consistently low (see figure). These four dams have significant impacts on endangered salmon, and environmentalists have long pushed to remove them. However, opposition from hydropower and barging interests have made this battle far from easy.